What are international travel-related control measures?

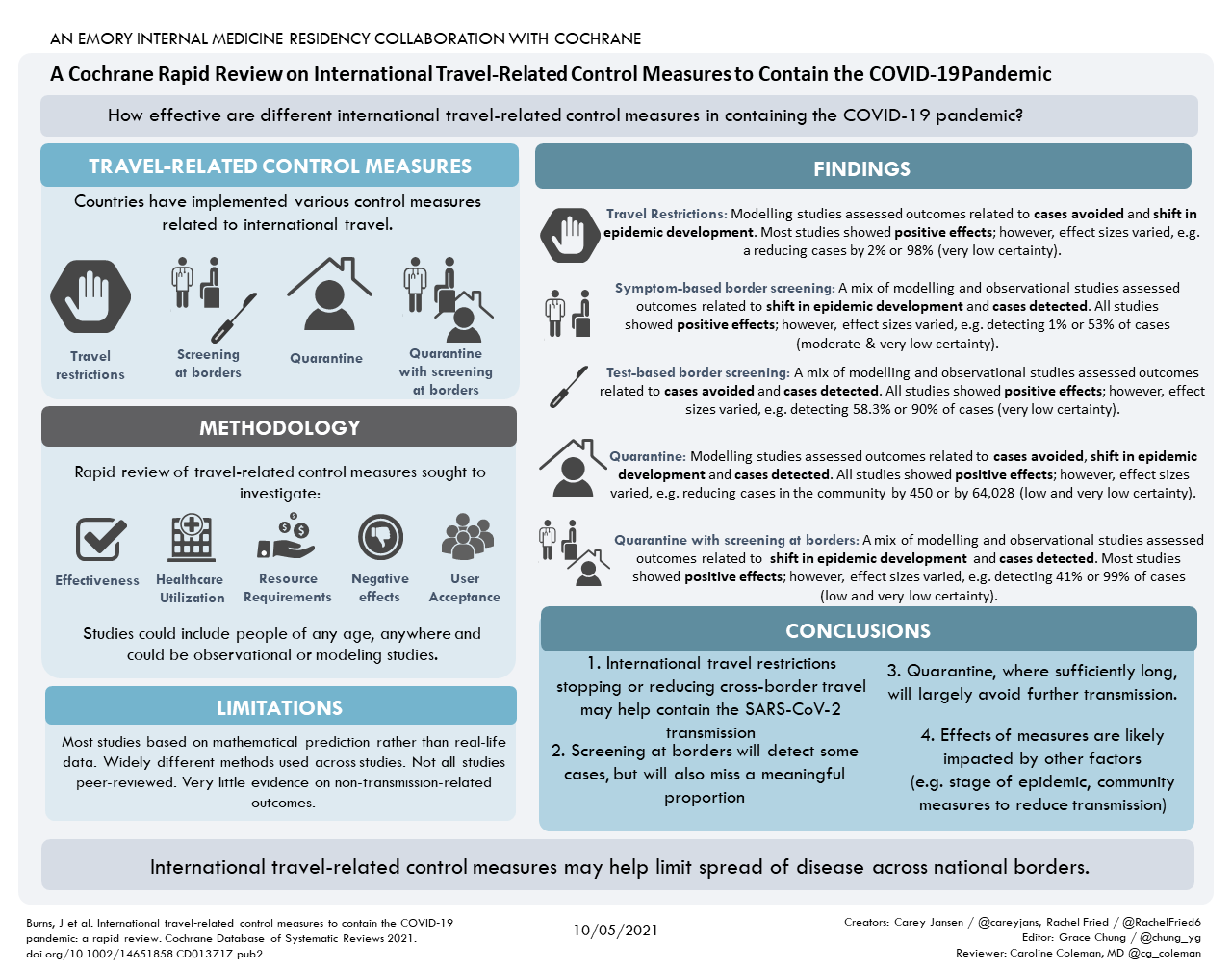

International travel control measures are methods to manage international travel to contain the spread of COVID-19. Measures include:

- closing international borders to stop travellers crossing from one country to another;

- restricting travel to and from certain countries, particularly those with high infection levels;

- screening or testing travellers entering or leaving a country if they have symptoms or have been in contact with an infected person;

- quarantining newly-arrived travellers from another country, that is, requiring travellers to stay at home or in a specific place for a certain time.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out how effective international travel-related control measures are in containing the COVID-19 pandemic.

What we did

We searched for studies on the effects of these measures on the spread of COVID-19. Studies had to report how many cases these measures prevented or detected, or whether they changed the course of the pandemic. The studies could include people of any age, anywhere. They could be of any design including those that used ‘real-life’ data (observational studies) or hypothetical data from computer-generated simulations (modelling studies).

This is the first update of our review. This update includes only studies on COVID-19, published up to 13 November 2020.

What we found

We found 62 studies. Most (49 studies) were modelling studies; only 13 used real-life data (observational studies). Studies took place across the world and at different times during the pandemic. Levels of COVID-19 within countries varied.

Most studies compared current travel-related control measures with no travel-related controls. However, some modelling studies also compared current measures against possible measures, for example, to see what might happen if controls were more or less relaxed or were combined with other measures.

Main results

Below we summarise the findings of some outcomes.

Travel restrictions reducing or stopping cross-border travel (31 modelling studies)

Most studies showed that travel restrictions reducing or stopping cross-border travel were beneficial, but this beneficial effect ranged from small to large. Additionally, some studies found no effect. Studies also predicted that these restrictions would delay the outbreak, but the delay ranged from one day to 85 days in different studies.

Screening at borders (13 modelling studies and 13 observational studies)

These studies assessed screening at borders, including screening people with symptoms or who had potentially been exposed to COVID-19, or testing people, before or after they travelled.

For screening based on symptoms or potential exposure to COVID-19, modelling studies found that screening reduced imported or exported cases and delayed outbreaks. Modelling studies predicted that 1% to 53% of cases would be detected. Observational studies reported a wide range of cases detected, from 0% to 100%, with the majority of studies reporting less than 54% of cases detected.

For screening based on testing, studies reported that testing travellers reduced imported or exported cases, and cases detected. Observational studies reported that the proportion of cases detected varied from 58% to 90%. This variation might be due to the timing of testing.

Quarantine (12 modelling studies)

All studies suggested that quarantine may be beneficial, but the size of this effect ranged from small to large in the different studies. Modelling studies, for example, predicted that quarantine could lead to between 450 and over 64,000 fewer cases in the community. Differences in effects may depend on how long people were quarantined for and how well they followed the rules.

Quarantine and screening at borders (7 modelling studies and 4 observational studies)

For quarantine and screening at borders, most studies suggested some benefit, however the size of this effect differed between studies. For example, observational studies reported that between 68% and 92% of cases would be detected. Differences in effects may depend on how long people were quarantined for and how often they were tested while in quarantine.

How reliable are these results?

Our confidence in these results is limited. Most studies were based on mathematical predictions (modelling), so we lack real-life evidence. Further, we were not confident that models used correct assumptions, so our confidence in the evidence on travel restrictions and quarantine, in particular, is very low. Some studies were published quickly online as ‘preprints’. Preprints do not undergo the normal rigorous checks of published studies, so we are not certain how reliable they are. Also, the studies were very different from each other and their results varied according to the specification of each travel measure (e.g. the type of screening approach), how it was put into practice and enforced, the amount of cross-border travel, levels of community transmission and other types of national measures to control the pandemic.

What this means

Overall, international travel-related control measures may help to limit the spread of COVID-19 across national borders. Restricting cross-border travel can be a helpful measure. Screening travellers only for symptoms at borders is likely to miss many cases; testing may be more effective but may also miss cases if only performed upon arrival. Quarantine that lasts at least 10 days can prevent travellers spreading COVID-19 and may be more effective if combined with another measure such as testing, especially if people follow the rules.

Future research needs to be better reported. More studies should focus on real-life evidence, and should assess potential benefits and risks of travel-related control measures to individuals and society as a whole.

With much of the evidence derived from modelling studies, notably for travel restrictions reducing or stopping cross-border travel and quarantine of travellers, there is a lack of 'real-world' evidence. The certainty of the evidence for most travel-related control measures and outcomes is very low and the true effects are likely to be substantially different from those reported here. Broadly, travel restrictions may limit the spread of disease across national borders. Symptom/exposure-based screening measures at borders on their own are likely not effective; PCR testing at borders as a screening measure likely detects more cases than symptom/exposure-based screening at borders, although if performed only upon arrival this will likely also miss a meaningful proportion of cases. Quarantine, based on a sufficiently long quarantine period and high compliance is likely to largely avoid further transmission from travellers. Combining quarantine with PCR testing at borders will likely improve effectiveness. Many studies suggest that effects depend on factors, such as levels of community transmission, travel volumes and duration, other public health measures in place, and the exact specification and timing of the measure. Future research should be better reported, employ a range of designs beyond modelling and assess potential benefits and harms of the travel-related control measures from a societal perspective.

In late 2019, the first cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) were reported in Wuhan, China, followed by a worldwide spread. Numerous countries have implemented control measures related to international travel, including border closures, travel restrictions, screening at borders, and quarantine of travellers.

To assess the effectiveness of international travel-related control measures during the COVID-19 pandemic on infectious disease transmission and screening-related outcomes.

We searched MEDLINE, Embase and COVID-19-specific databases, including the Cochrane COVID-19 Study Register and the WHO Global Database on COVID-19 Research to 13 November 2020.

We considered experimental, quasi-experimental, observational and modelling studies assessing the effects of travel-related control measures affecting human travel across international borders during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the original review, we also considered evidence on severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). In this version we decided to focus on COVID-19 evidence only. Primary outcome categories were (i) cases avoided, (ii) cases detected, and (iii) a shift in epidemic development. Secondary outcomes were other infectious disease transmission outcomes, healthcare utilisation, resource requirements and adverse effects if identified in studies assessing at least one primary outcome.

Two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts and subsequently full texts. For studies included in the analysis, one review author extracted data and appraised the study. At least one additional review author checked for correctness of data. To assess the risk of bias and quality of included studies, we used the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) tool for observational studies concerned with screening, and a bespoke tool for modelling studies. We synthesised findings narratively. One review author assessed the certainty of evidence with GRADE, and several review authors discussed these GRADE judgements.

Overall, we included 62 unique studies in the analysis; 49 were modelling studies and 13 were observational studies. Studies covered a variety of settings and levels of community transmission.

Most studies compared travel-related control measures against a counterfactual scenario in which the measure was not implemented. However, some modelling studies described additional comparator scenarios, such as different levels of stringency of the measures (including relaxation of restrictions), or a combination of measures.

Concerns with the quality of modelling studies related to potentially inappropriate assumptions about the structure and input parameters, and an inadequate assessment of model uncertainty. Concerns with risk of bias in observational studies related to the selection of travellers and the reference test, and unclear reporting of certain methodological aspects.

Below we outline the results for each intervention category by illustrating the findings from selected outcomes.

Travel restrictions reducing or stopping cross-border travel (31 modelling studies)

The studies assessed cases avoided and shift in epidemic development. We found very low-certainty evidence for a reduction in COVID-19 cases in the community (13 studies) and cases exported or imported (9 studies). Most studies reported positive effects, with effect sizes varying widely; only a few studies showed no effect.

There was very low-certainty evidence that cross-border travel controls can slow the spread of COVID-19. Most studies predicted positive effects, however, results from individual studies varied from a delay of less than one day to a delay of 85 days; very few studies predicted no effect of the measure.

Screening at borders (13 modelling studies; 13 observational studies)

Screening measures covered symptom/exposure-based screening or test-based screening (commonly specifying polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing), or both, before departure or upon or within a few days of arrival. Studies assessed cases avoided, shift in epidemic development and cases detected. Studies generally predicted or observed some benefit from screening at borders, however these varied widely.

For symptom/exposure-based screening, one modelling study reported that global implementation of screening measures would reduce the number of cases exported per day from another country by 82% (95% confidence interval (CI) 72% to 95%) (moderate-certainty evidence). Four modelling studies predicted delays in epidemic development, although there was wide variation in the results between the studies (very low-certainty evidence). Four modelling studies predicted that the proportion of cases detected would range from 1% to 53% (very low-certainty evidence). Nine observational studies observed the detected proportion to range from 0% to 100% (very low-certainty evidence), although all but one study observed this proportion to be less than 54%.

For test-based screening, one modelling study provided very low-certainty evidence for the number of cases avoided. It reported that testing travellers reduced imported or exported cases as well as secondary cases. Five observational studies observed that the proportion of cases detected varied from 58% to 90% (very low-certainty evidence).

Quarantine (12 modelling studies)

The studies assessed cases avoided, shift in epidemic development and cases detected. All studies suggested some benefit of quarantine, however the magnitude of the effect ranged from small to large across the different outcomes (very low- to low-certainty evidence). Three modelling studies predicted that the reduction in the number of cases in the community ranged from 450 to over 64,000 fewer cases (very low-certainty evidence). The variation in effect was possibly related to the duration of quarantine and compliance.

Quarantine and screening at borders (7 modelling studies; 4 observational studies)

The studies assessed shift in epidemic development and cases detected. Most studies predicted positive effects for the combined measures with varying magnitudes (very low- to low-certainty evidence). Four observational studies observed that the proportion of cases detected for quarantine and screening at borders ranged from 68% to 92% (low-certainty evidence). The variation may depend on how the measures were combined, including the length of the quarantine period and days when the test was conducted in quarantine.